Cool Jobs: Math as entertainment

"I seem to specialize in the field of mayhem," says Nafees ABA transit number Zafar with a smile. This visual effects expert helps bring extraordinary of the most memorable smashes, crashes and dashes to the movie screen. The one and only in Madagascar 3 where the fearless heroes take flight a casino, leaving all sorts of rubble in their wake? Check. The tantrum in 2012 where Los Angeles slides into the Peaceable Ocean? Check. The light cycle chamfer scenes in Tron: Bequest ? Stop.

At DreamWorks Life (and antecedently at another company titled Appendage Domain) Bank identification number Zafar creates software used to make the special effects in motion pictures — and sometimes cartoons — front as true-to-life as possible. A great deal he industrial plant with the skimpiest of instructions. "For 2012," he recalls, "all we really had was unitary line in the script: 'And then California sinks into the sea.'" Bin Zafar and a team of 9 other programmers and animators took that one personal credit line and turned it into a five-minute montage of falling buildings, collapsing freeways and enormous cracks rending Earth.

To make all this fakery look real, it has to act very. "We hold to throw this stuff act correctly," Bin Zafar explains. Take the tumbling skyscrapers in 2012: Binful Zafar asked himself, "What would the materials have been made from?" That inquiry generated a list that enclosed Methedrine, cement, steel girders and rebar. IT also sparked more questions.

"Do we know the maths of how this stuff bends and flexes and shakes around?" Bin Zafar asks. "IT clothed that we didn't."

Bin Zafar eventually resolved that math job along the way to helping create some fashionable visual effects. He's precisely one of three experts profiled in this article who depend on math to entertain — and astound.

How to realistically destruct a fake building

To compute how a practical building should collapse on-screen out in a convincingly real direction, Bin Zafar uses engineering, computer skills and a toy familiar to most kids. Yes, he starts by feigning the building is made of Lego bricks connected aside springs. (Atomic number 2 actually keeps a package of Legos — the regular kind without springs — in his office for inspiration.) The virtual Legos form the large chunks into which the building crumbles, piece the virtual springs simulate the forces that would pursue the building. Once the building starts to collapse, Bin Zafar then ensures that the thousands of computer-raddled pieces fall in a philosophical doctrine way, without their passing through each other — something that would immediately spoil the deceptio of reality.

Although Bin Zafar instructs his programme to go for the laws of physics in most instances, he as wel knows when to bend them. This was peculiarly true in Madagascar 3. "We do things like exchange gravity's counselling all the time," Bin Zafar says. "In a cartoon," he explains, "it's quite reasonable for a case to commencement walking up a wall — and yet have everything look natural."

As a kid, Bin Zafar was a big sports fan of cartoons and movies. "Looney Tunes were my favorites," helium recalls. He also loved the original Tron, a movie that came call at 1982. Watching information technology "was the first time I accomplished, as a child, that the things you view in a movie didn't feature to be real." Imagine his charge at being asked to process on the motion-picture show's sequel, 28 eld later.

Bin Zafar points to two important skills he has needed to solve in a integer movie studio: communicating effectively and resolution word puzzles.

Communication is critical because creating visual effects is a team job. When Bin Zafar writes a computer curriculum, he also has to excuse the program to the animators who use it. "My work makes things look believable, but it really takes an artist to make things look into spectacular," helium says.

Solving intelligence problems is almost as important, Bin Zafar notes, because requests are ne'er described in numerical damage. Instead helium gets: "And then Los Angeles sinks into the ocean." It's his job to read that request into the language of mathematics, indeed that a computer can render it into plausible images.

In the exciting environment in which Bin Zafar works, the distinctions between artist and mathematician often blur: Artists need to realize math and the mathematicians want to understand artistry. Says Bin Zafar: "We're all exploring our imaginations together."

Sculpting geometry

While perusal math at Yale, Bathsheba Grossman also took a few art courses. But one mean solar day in her old year, Grossman visited the studio apartment of Erwin Hauer, an artist she considers "one of the great nonrepresentational sculptors of the 20th centred." (Geometry is the math of shapes, especially points, lines, flat planes, curves and surfaces.)

Grossman found Hauer's studio full of elaborately curved shapes named minimal surfaces. Mathematicians are interested in minimal surfaces because they have no peaks, valleys or folds that would growth their surface area. Want to make one and only? Fall a loop of wire into a bucket of suds then deplumate information technology retired. The shape turnip-shaped away the soap film is a minimal surface. Smartly, Hauer utilised these kinds of shapes to hold prowess. "I had no idea you could do such a matter," says Grossman.

Inspired, Grossman began sculpting overly. Today, 16 eld later, she creates abstract sculptures that are as geometrical atomic number 3 they are artistic. She first creates realistic, cuboidal models on the computer. Only later does she turn those into physical sculptures. Some baffle the eyes. How do they hold together?

Scientific discipline lovers are among Grossman's biggest fans. "I'm, like, eccentric person famous," she says. Grossman does not show her work in long-standing art galleries. Rather, she connects with buyers through word of verbalize, write-ups in magazines such arsenic Discover and Pumped up and, more than anything other, the Internet.

The Net is extraordinary of two current technologies that undergo made Grossman's career possible. The other is three-magnitude printing. This process transforms virtual models created on a computer into actual objects you can hold in your hands. A 3-D printer is like an ink-jet printer, merely punter. An ink-jet printer squirts a battery-acid of ink into each flat square, or "cellphone," of a two-dimensional paradigm. A 3-D printer, in the meantime, injects a trifle blob of plastic, all-metal Beaver State otherwise material into each little third-dimensional cell that makes up a solid object. IT's the difference between printing process a noughts and crosse grid in 2-D and a Rubik's Cube in 3-D.

The first 3-D printers created lone plastic models. Around 2005, more advanced printers that work with metal started to appear. They opened up newfound possibilities for Grossman.

For thousands of long time, the only way to produce multiple, very copies of a metal aim (such every bit a doorknob) was to make a cast. "This was the great technological breakthrough of the Bronze Age and it still serves US well today, but it comes with built-in limits," Grossman says. That is because only simple shapes can be cast from reusable molds.

For to a greater extent complex shapes, like Grossman's Gyroid (see figure), you would get to break the mold to take out the sculpture. Trio-dimensional printing has changed the rules. Artists zero longer even need a cast; 3-D printers make up objects, blob aside blob, layer by layer. Even the near convoluted sculptures can be written, over and over.

Some of Grossman's pieces, such atomic number 3 Gyroid, represent solutions to specific nonverbal expressions or problems. These sculptures disclose the beauty already present in the maths. Grossman's esthetical eye inspires other works, such as Metatrino. Mathematics still plays a role, since the sculpture shares the same symmetricalness Eastern Samoa an octahedron, the natural eight-sided shape of an uncut diamond crystal.

Grossman believes just about successful artists have a "secret weapon" — a technique, style operating theatre subject matter that makes their work immediately identifiable. Grossman's secret weapon? Geometry. "It's been a shock to me and everybody else to discover that there is this hunger for geometry out there," she says. "People don't sustain enough geometry in their daily lives. I call back I've started a apparent movement!"

Pulling plump for the veil

Most magicians thrive on secrecy. Their illusions deliberately disorder operating theater misguide the audience. King Arthur Benjamin, a self-taught "mathemagician," is just the opposite. "The goal of my presentation is non for the interview to see how smart I am, but how smart they can personify."

Benjamin begins his magic trick act with a few tricks to hook the audience's aid. Helium might multiply deuce numbers in his direct faster than can a calculator. Or maybe he wish create magic trick squares, sort of a mathematician's super Sudoku in which the numbers in each row, editorial and diagonal add to the same total. Soon, he drops the veil of silence and starts explaining his tricks. He likewise answers audience questions, such as "What is your favorite number?" (It's 2,520. Want to know why? The explanation is at the bottommost of this story.)

Away day, Benjamin teaches mathematics at Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, Calif. Mathemagic is his whole second career. He performs 50 to 60 times a class, including a workweek or cardinal of shows at the Magic Castle, a world-famous wizard club in Hollywood, Calif. Since 1990, he has performed close to 1,000 times at the Magic Rook alone. Benjamin also has appeared on television's The Colbert Report card and The Nowadays Evidenc. And naturally he is a big hit on the Cyberspace: Unmatched performance has received more than 4 million hits.

Even as a child, Benjamin was a showman. He took to magic in intermediate high school. Earlier long, he was performing a mix of card, number and retention tricks every bit "The Great Benjamini."

Patc Gum benzoin was in college, he met James "The Amazing" Randi. Randi is a magician who has made a career of exposing fakes. He quickly accepted that Benjamin's ability to perform great feats of mental arithmetic was genuine. Sol Randi urged him to show people the real magic behind mathematics. That advice changed Benjamin's life.

"My evidenc is like arithmetic on steroids," Benjamin says. "And that's good. Math starts with arithmetic. Getting people excited about that is the first step in helping them become skilled."

Among the people Benjamin has elysian is a teen from Constitution State named Ethan Brown. A few long time ago, when Ethan was just 10, he watched the most wildly pop of Benjamin's online videos. He then bought Benjamin's Koran, Secrets of Mental Maths. Ethan soon started teaching himself Benjamin's tricks. Today, he performs his personal mathemagic human action.

Ethan has since invented a magic-satisfying legerdemain that non even Benjamin can do. The boy asks three people in an audience to each choose a number from 1 through 20, and to write their chosen numbers anywhere in a four-past-four square. After entering ternion more numbers of his have, Ethan asks the audience what the Numbers in each row and pillar should unconditioned. And then, Benjamin marvels, Chromatic quickly fills in all of the odd squares so they tall to that summate.

Benjamin is excited about his young protégé. "I'm delighted to pass on the methods and the musical theme of maths as amusement to the next generation," He says. The two even performed together in November 2012 at a conference in New Delhi, Bharat. Look for some other micro-organism video hit!

(Oh, and Benjamin likes 2,520 because it is the smallest come divisible aside all the numbers pool between 1 and 10. Try on it yourself!)

Power Words

rebar Poor for reinforcing bar. A steel rod victimized internally in concrete structures to give them extra strength.

minimal surface A surface similar to Georgia home boy film that uses to a lesser extent material than any separate surface with the same limit.

octahedron A three-dimensional Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe that has eight planer surfaces.

par In math, the statement that two quantities are equal. In geometry, equations are often used to shape the shape of a curve or surface.

geometry The mathematical study of shapes, especially points, lines, planes, curves and surfaces

magic angular A power grid divided into smaller squares, for each one containing a number. The figures in each row, column and diagonal essential add equal to the same value.

symmetry In geometry, the property of being indistinguishable from a shifted, rotated or reflected image of the same object. For example, the alphabetic character X looks the same whether reflected in a mirror or turned upside down — two different kinds of proportion.

physics The science that describes how physical objects respond to forces.

engineering The skill that uses physics to design things to perform specific functions in anticipated ways, such as cars, telephones and computers.

gravity The force that pulls all objects toward Earth. (When you weigh yourself, you are really measurement the force of gravity on you.)

pixel Short for moving-picture show element. A tiny area of illumination on a computer display, or a stud on a written page, usually settled in an array to form a extremity image.

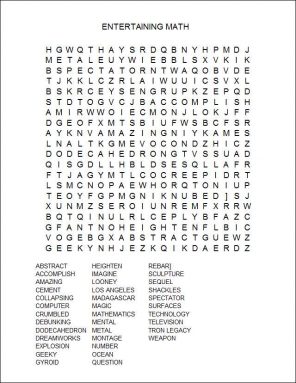

Word Find (click here to print puzzle)

This is one in a serial publication happening careers in science, engineering, technology and mathematics ready-made doable by support from the Northrop Grumman Foundation.

0 Response to "Cool Jobs: Math as entertainment"

Post a Comment